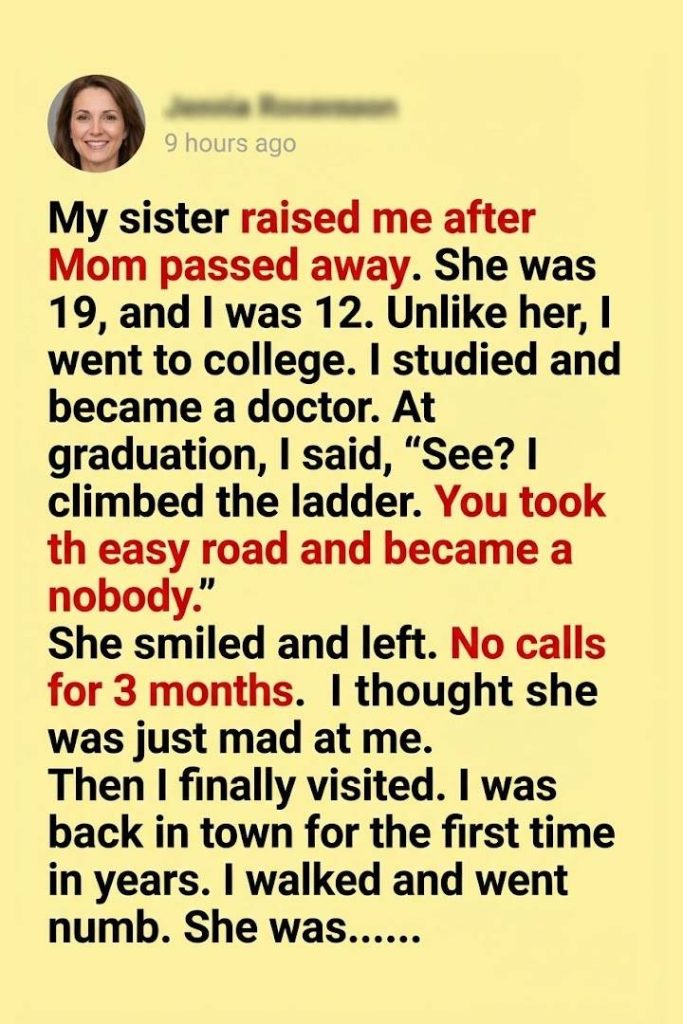

My sister raised me after Mom passed away.

She was nineteen. I was twelve.

One day she was worrying about exams, friends, and what to wear to a party. The next, she was signing school forms, meeting teachers, and standing in a funeral home trying to choose flowers she couldn’t afford. Grief didn’t come gently to us. It arrived like a storm that tore the roof off our lives and left her holding the pieces together with hands that were still supposed to be young.

Overnight, she stopped being a teenager.

She dropped out of school before the semester even ended. I remember overhearing her on the phone with the counselor, her voice steady as she said, “I’ll come back someday.” We both knew she wouldn’t. She picked up shifts at a diner during the day and cleaned office buildings at night. She learned how to stretch one chicken into three meals, how to sew holes in my jeans so neatly no one at school noticed, how to smile like she wasn’t bone-tired.

I was the one everyone said had “potential.”

Teachers said it at conferences. Neighbors said it over fences. Relatives said it with that meaningful nod, as if my future were a shiny thing they could already see. “He’s going to do big things,” they’d tell her, and she’d glow like they’d complimented her instead. So she made sure I never missed a class. Never missed a meal. Never felt the weight she carried on her narrow shoulders.

She hid the overdue notices. She hid the eviction warnings until the last possible moment. She hid her coughs, the ones that bent her in half when she thought I was asleep.

Unlike her, I went to college.

The day I left, she hugged me so tight I could feel her ribs. “Don’t look back,” she said into my shoulder. “Just go.” I thought she meant don’t be sad. I didn’t realize she meant don’t let guilt drag you down. So I went. I studied while she worked. I complained about exams while she pulled double shifts. I called sometimes, but less and less as my world got bigger.

Years passed in a blur of lectures, labs, internships. I kept going. Medical school. Residency. Sleepless nights, endless coffee, the constant pressure to prove I belonged. Whenever things felt impossible, I’d remember her voice: You can do this. You’re meant for more. So I pushed through.

And I became a doctor.

At my graduation, the auditorium was packed. People clapped. Professors praised me. My name echoed through the hall, followed by a list of honors that sounded surreal. I felt ten feet tall walking across that stage, my gown swaying, the weight of the stethoscope in my pocket like a medal.

Relatives crowded around afterward, shaking my hand. “We always knew,” they said. “Your sister must be so proud.”

I found her in the crowd—standing off to the side, as always. She wore the same simple blue dress she’d owned for years, the fabric faded at the seams. Her hair was pulled back in a quick ponytail, dark circles under her eyes she’d tried to hide with makeup.

I was high on pride, on relief, on the intoxicating feeling of having made it. I laughed and said the words that still wake me up at night.

“See? I climbed the ladder. You took the easy road and became a nobody.”

Even as I said it, part of me knew it sounded wrong. But ego is loud, and gratitude is quiet. I thought I was joking, teasing, celebrating the difference between us like it was proof the sacrifice had worked.

She didn’t argue.

She didn’t cry.

She just smiled softly… and left.

No dramatic scene. No lecture. She slipped out of the auditorium while I was busy taking photos, shaking hands, being congratulated for a future she had paid for.

Three months passed without a call.

I noticed, but I told myself she was just hurt. That she’d get over it. That I’d apologize someday—when things slowed down. When residency wasn’t so brutal. When I had the right words. There’s always a later, until there isn’t.

Eventually, I had a rare weekend off and decided to visit. First time back in town in years.

The streets felt smaller. The houses older. I drove past our old school, the park where she used to push me on the swings after work even when her eyes looked half-closed. My chest tightened with memories I had filed away as “before.”

I walked up to her apartment building—and felt my legs go weak.

Her name wasn’t on the mailbox.

I stood there longer than I should have, staring at the row of metal slots as if her name might reappear if I blinked enough. Finally, I went inside and asked the landlord, an older man who used to wave at us when we left in the mornings.

He looked at me with a kind of pity I recognized from hospital corridors.

“She moved out months ago,” he said. “Couldn’t keep up with the rent after her health went downhill.”

My chest went numb.

“Health?” I repeated. The word felt foreign in relation to her. She was the strong one. The unbreakable one.

I tracked her down through an old coworker to a small care facility on the edge of town. The building was low and quiet, the kind of place people ended up when life had worn them down too far.

When I walked into her room, I barely recognized her.

She was thinner, her face sharper, skin pale against the hospital pillow. Tubes ran from her arm. Machines hummed softly beside the bed. But when she turned her head and saw me, her smile was the same.

“Hey, kiddo,” she said, like I’d just come home from school. “You look tired. Are you eating enough?”

That broke something in me.

I sat beside her, my medical training screaming details I didn’t want to see. The lab reports at the foot of her bed. The late-stage diagnosis. The signs of years of ignored symptoms—fatigue, pain, shortness of breath she must have brushed off because there was always another shift, another bill, another need that wasn’t hers.

That’s when I learned the truth.

She’d been working nights for years. Skipping doctor visits because she didn’t have time, or insurance that covered enough. Ignoring symptoms that would have sent anyone else to a clinic. By the time she collapsed at work, it was too late. The disease had spread quietly, patiently, while she poured everything into keeping my path clear.

I sat there in my white coat, the symbol of everything I’d achieved, and felt like an imposter.

“I’m sorry,” I said, over and over, the words small and useless. “I didn’t know. I should have—”

She squeezed my hand with surprising strength.

“I never wanted you to know,” she whispered. “You had enough to carry.”

Tears blurred my vision. “I called you a nobody,” I choked. “After everything.”

She smiled, that same soft smile from graduation day. “You were just talking. You’ve always had big words.” She paused, catching her breath. “I never needed to be somebody. I just needed you to be okay.”

She passed away two weeks later.

I was there at the end, holding her hand the way she’d held mine crossing streets when I was small. The monitors went quiet. The room felt impossibly still. For the first time since I was twelve, I was alone in the world in a way that mattered.

I’m a doctor now. People call me successful. They praise my dedication, my long hours, my compassion with patients. They say I climbed far, that I made something of myself.

But every time someone says it, I see her at nineteen, signing withdrawal papers. I see her at twenty-two, counting tips at the kitchen table. I see her at thirty, coughing into a towel so I wouldn’t hear.

Every step I took up that ladder, she was underneath it, holding it steady with her own life.

And I know exactly who the real hero was.